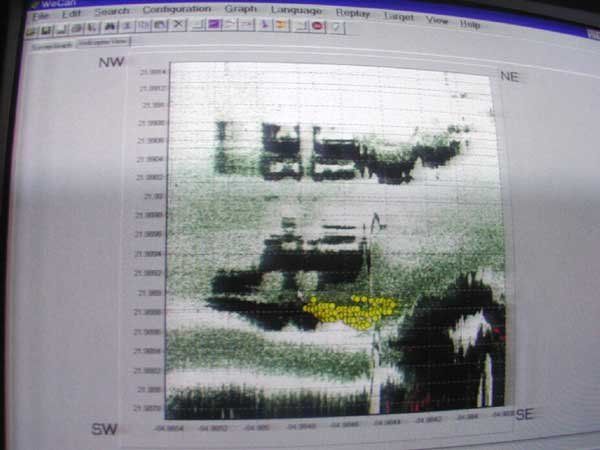

In 2001, a team of explorers made an incredible discovery in the sea surrounding the island of Cuba. Off the country’s western coast, about 650 meters below the surface, researchers used advanced sonar equipment to identify large stone structures that had previously been unknown to the world.

The exploration mission, sponsored by the Cuban government during the communist regime of Fidel Castro, led many to question whether the finding could be a sort of Latin American Atlantis. This comparison arose mainly from the fact that the discovered stones were arranged in a way that seemed to suggest some form of urban development before the area was submerged.

Naval engineer Pauline Zalitzki and her husband, Paul Weinzweig, owners of Advanced Digital Communications (ADC), the company responsible for the discovery, were hired by Castro to explore Cuban waters, where many Spanish ships sank during the European colonization of the Americas. In addition to holding numerous treasures, these vessels could also provide further insight into the continent’s colonial history.

The submerged “city” is located on the Guanahacabibes Peninsula, in Pinar del Río Province, at the westernmost tip of Cuba. Although it was discovered in 2001, more than two decades ago, it still sparks interest among enthusiasts and experts on the subject. However, few—if any—studies on the site are currently being conducted.

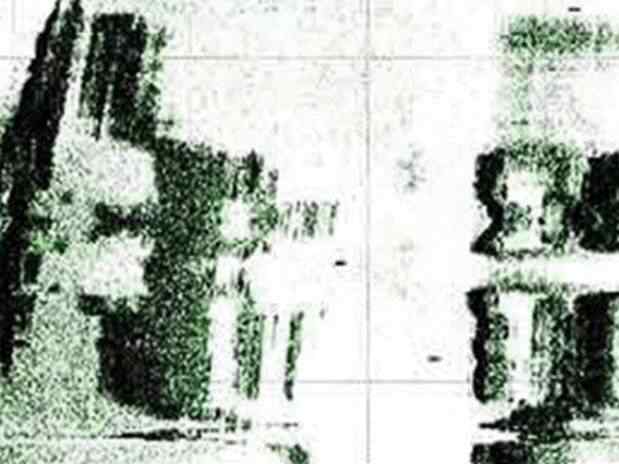

The images generated by the scanning equipment showed smooth, symmetrically arranged stones, resembling urban development, BBC News reported at the time.

In the same year as the discovery, the ADC team — led by marine engineer Pauline Zelitsky and her husband Paul Weinzweig — returned to the site with an exploratory robotic device capable of conducting advanced underwater filming. The footage captured confirmed the presence of smooth blocks resembling cut granite, some measuring 2.4 by 3 meters, as well as other geometric shapes. Some of the stones appeared stacked, resembling pyramids, while others were circular.

Zelitsky, Weinzweig, and their colleagues deduced that these formations might have been built over 6,000 years ago — 1,500 years before the great pyramids of Egypt. They suggested that the buildings may have been constructed on land before being submerged by the sea, possibly due to volcanic activity in the area. “The structures we found on the side-scan sonar simply cannot be explained from a geological standpoint,” Weinzweig told the South Florida Sun-Sentinel in 2002. “There is so much organization, so much symmetry, so much repetition of shape.”

Even so, Zelitsky was quick to insist that more research was needed before any definitive conclusions could be drawn. “It’s a really wonderful structure that looks like it could have been a large urban center,” Zelitsky told Reuters at the time. “However, it would be entirely irresponsible to say what it was before we have evidence.”

Thus, more evidence was sought by experts, including geologist Manuel Iturralde, then a senior researcher at the Cuban Museum of Natural History. Iturralde, who had studied numerous underwater formations, admitted: “These are extremely peculiar structures and captured our imagination.” He also noted that volcanic rocks recovered at the site strongly suggested that the underwater plain was once above the water, as reported by the Washington Post in 2002. The marine geologist stated that the existence of these rocks is difficult to explain, especially since there are no volcanoes in Cuba. Yet, he also acknowledged: “Nature is much richer than we think.”

Iturralde pointed out that the depth at which the structures were found posed a challenge to the “lost city” theory. He estimated that, at the maximum speed of Earth’s tectonic movements, it would take 50,000 years for the ruins to sink 650 meters underwater.

However, he emphasized: “50,000 years ago, there was no architectural capacity in any of the cultures we know to build complex buildings.” Michael Faught, an underwater archaeology expert from Florida State University, shared similar doubts with the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. He told the newspaper: “It would be nice if [Zelitsky and Weinzweig] were right, but it would really be too advanced for anything we would see in the New World for that time period. The structures are out of time and out of place.”

Despite this, the news of the discovery quickly triggered a wave of excitement, with commentators suggesting that these could be the remains of none other than the legendary continent of Atlantis. Still, Zelitsky was quick to deny this idea, emphasizing that Atlantis is pure myth, insisting: “What we found are probably remnants of a local culture.” She suggested that the site may have been part of a 160-kilometer “land bridge” that connected the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico to Cuba, as reported by Ancient Origins.

Meanwhile, Iturralde pointed out local legends told by the Mayans and Yucatán natives about an island inhabited by their ancestors that disappeared beneath the waves. However, the depth of the discovery continued to discredit such theories in the eyes of many people.

In 2012, Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews, the administrator of the Bad Archaeology site, pointed out that during the Pleistocene era, which lasted from 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago, sea levels dropped by a maximum of about 100 meters (328 feet). “At no point during the Ice Age would [the Cuban ruins] have been above sea level, unless, of course, the land they are on had sunk,” wrote Fitzpatrick-Matthews. He also compared the claim to Plato’s story of Atlantis, which was destroyed by “violent earthquakes and floods.” According to Fitzpatrick-Matthews, the violence of the shipwreck makes it unlikely that an entire city could have survived sinking more than 600 meters.

In 2016, researcher Brad Yoon, in Ancient Origins, questioned whether the Caribbean Sea might have been a “dry basin” during modern man’s time, where the city was built. However, after an exhaustive search, he could not find any source presenting this hypothesis. He concluded that if true, the idea would explain how a city could have been built 700 meters below sea level.

Despite all the speculation, the true nature of the structures remains a mystery. More than two decades after the discovery, the lack of follow-up research persists. Several planned expeditions were canceled due to funding problems or blockades imposed by the Cuban government. Bureaucracy and logistical challenges have hindered significant progress. However, the discovery remains proof that our knowledge of humanity’s past should be constantly revised. As Weinzweig said in 2002, “We believe that much of the significant archaeology of the future will be discovered in the oceans of the unexplored world and will greatly expand our understanding of the vast antiquity of human civilization.”

The discovery of the mysterious submerged structures off the coast of Cuba remains an enigma for researchers, raising numerous unanswered questions about human history. The lack of subsequent research and the logistical, political, and financial obstacles have hindered a full unraveling of this mystery. Over time, the project lost momentum, and planned expeditions were canceled, with no new evidence or clear conclusions emerging. However, the lack of continuity in the investigations raises an important question: what might we be losing by not exploring and understanding this discovery more thoroughly?

If these submerged structures are indeed the remnants of an ancient, lost, and advanced civilization, it could rewrite the known history of humanity, altering our understanding of the cultural and technological development of our ancestors. The absence of in-depth analysis of these remains not only prevents the confirmation of one theory but also leaves open the possibility of discoveries that could connect our origins to long-forgotten civilizations.

The lack of continuity in the research can also be seen as a missed opportunity for humanity to better understand the mysteries of the past and, thus, shape a richer narrative about the roots of civilization. Without a coordinated effort to scientifically and impartially investigate and analyze the submerged structures, we risk leaving these discoveries as mere curiosities or speculations when they could actually provide valuable data for global history.

What is lost by ignoring or abandoning such investigations is not just the chance to solve a mystery but the opportunity to expand our knowledge about ancient civilizations, their capabilities, and their possible connections with other peoples. What really happened with the submerged city of Cuba, and what could it reveal about human evolution if more studies were conducted? This is a question that may never be fully answered, but by ignoring it, we leave a significant gap in understanding our own history.