Göbekli Tepe, located in southeastern Turkey near the city of Şanlıurfa, is a Neolithic archaeological site dating back approximately 11,000 years. It was discovered in the 1960s, but its remarkable features only began to be studied in depth from the 1990s under the leadership of Klaus Schmidt.

The site is remarkable in many respects: its location is hostile to human habitation, with no nearby water sources; there is no clear evidence of domestic buildings so far in Layer III; only a limited selection of material culture is present (very few bone tools, and clay figurines are absent); and a considerable investment of resources and labor is evident. This investment was not limited to the construction of Göbekli Tepe alone.

At the end of their functional lives, all buildings in Layer III (PPN A, 10th millennium BCE) were at least partially intentionally backfilled. The fill consists of limestone debris from Neolithic quarry areas on the adjacent plateaus, mixed with large quantities of animal bones, flint fragments, artifacts, and tools. Prior to backfilling, the buildings appear to have been carefully cleaned. If roofs existed, they were dismantled at that time, as no traces of them have been found.

Backfilling is clearly a limiting factor in our understanding of the enclosures’ function, as very few in situ deposits remain from the buildings’ period of use. However, the backfilling process appears to have been highly structured, involving deliberate actions. Among these, the deposition of artifacts and sculptures within the fill, often near the pillars, is particularly striking.

Therefore, at Göbekli Tepe, we do not know much about the exact period during which the buildings were used. However, we do have the enclosures themselves, their layout, and the richly decorated pillars as starting points. We also know a great deal about what people did with these enclosures at the end of their functional lives. It appears that they sought to highlight certain aspects of the enclosures’ significance through their actions.

There are several different categories of human representations at Göbekli Tepe. The most striking are the T-shaped pillars. The T-shape is clearly an abstract representation of the human body viewed from the side. Evidence for this interpretation includes low-relief depictions of arms, hands, and clothing items such as belts and loincloths on some of the central pillars.

There is a clear hierarchy of pillars within the enclosures. The central pillars reach up to 5.5 meters in height and display the anthropomorphic elements described above. The surrounding pillars are smaller but are more richly decorated with animal reliefs than the central ones. They are always “facing” the central pillars, and the benches between them further reinforce the impression of some sort of gathering.

Whether these represent ancestors of different importance, or even deities, is a separate topic, and a definitive answer is difficult to provide at present. What is clear, however, is that both the central and surrounding pillars share the same abstract form. This abstraction is not due to the Neolithic peoples’ limited ability to depict the human body, but rather a deliberate choice imbued with meaning.

Another important category of representations at Göbekli Tepe consists of more naturalistic sculptures. So far, a total of 143 sculptures have been found at the site. Of these, 84 depict animals, 43 humans, 3 phalli, and 5 are composite sculptures of humans and animals. It is striking that most anthropomorphic sculptures are fragmented. Of the 43 human representations, only 9 can be considered complete if minor damage is disregarded.

Another remarkable point is that, despite extensive excavations, there is only one case where sufficiently complete fragments were found for reconstruction. A closer examination of the preserved fragments reveals a pattern: the most commonly preserved parts are heads, not the generally larger torsos. The large number of broken heads and the regular fractures strongly suggest intentional fragmentation.

Furthermore, the heads were not discarded randomly. They were carefully deposited in the enclosures’ fill, often next to pillars. This treatment is similar in this respect to the deposition of zoomorphic sculptures, indicating a deliberate pattern of placement.

However, zoomorphic representations are mostly found intact, with no signs of intentional damage. Therefore, while the deposition patterns are similar, the pre-deposition treatment is not. Human heads appear to have played a special role in the beliefs associated with the Göbekli Tepe enclosures.

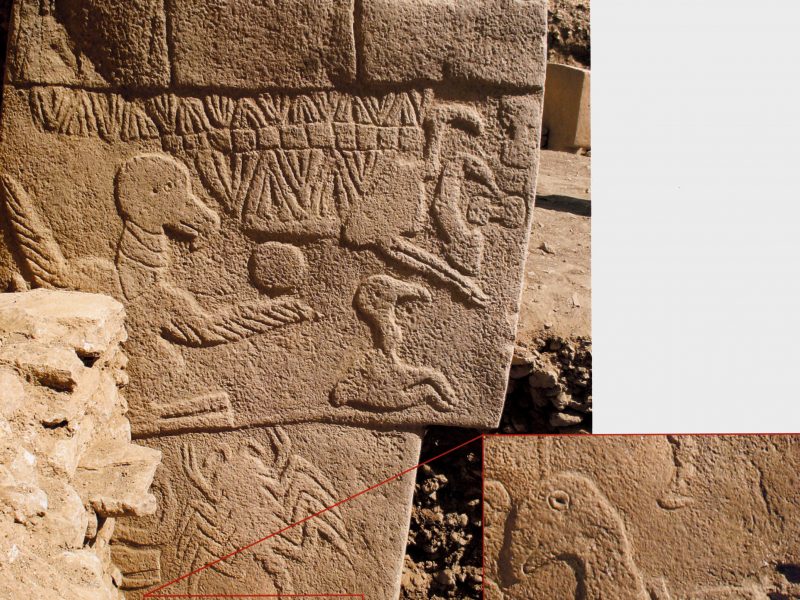

The special role of detached human heads is also visible in the reliefs at Göbekli Tepe. Immediately behind the eastern central pillar of Enclosure D, a relief fragment was found showing a human head among several animals – a vulture and a hyena can be clearly identified. Another example is Pillar 43, also in Enclosure D, where a headless ithyphallic body is depicted among several birds, snakes, and a large scorpion.

The interaction of animals with human heads is even more evident in several composite sculptures discovered at Göbekli Tepe. These sculptures depict birds, as well as quadrupeds sitting on or carrying human heads. Such iconography is clearly and significantly related to rites and mortuary cult practices of the Early Neolithic.

The special treatment and removal of skulls are well documented for the PPN (Pre-Pottery Neolithic). One of the most notable examples is the skull constructions at Çayönü. At this site, the situation is quite the opposite of Göbekli Tepe. There are many burials but only a few anthropomorphic representations. At Nevali Çori, burials with separate skulls were discovered, in one case with a flint dagger still in place, but also an image very similar to Göbekli Tepe. For example, the so-called totem pole shows a bird perched on a human head. There is also a larger number of limestone heads at Nevali Çori, reflecting the situation at Göbekli Tepe to some extent. Clearly, the special treatment of human heads can also be observed at many sites in the southern Levant, as well as at Köşk Höyük and Çatalhöyük. At Çatalhöyük, many of the elements seen at Göbekli Tepe are still present in a much later context. This includes iconography of birds carrying human heads, special treatment of heads in burials, and figurines with intentionally broken heads, or heads designed from the start to be removed.

In summary, at Göbekli Tepe there is evidence of a hierarchy of anthropomorphic representations. The central pillars of the enclosures are abstract and clearly characterized as anthropomorphic by arms, hands, and clothing elements. The surrounding pillars are also abstract but smaller, and mainly display zoomorphic decorations. They face the central pillars and evoke the impression of a gathering.

Naturalistic anthropomorphic sculpture is smaller and intentionally fragmented. During the backfilling of the enclosures, a selection of fragments, mainly heads, was placed within the fill, most often near the central pillars. This practice strongly evokes elements of Neolithic mortuary cults, which are also reflected in the iconography at Göbekli.

It appears that the abstract pillar-beings represent a different sphere from the naturalistic sculptures. Zoomorphic and anthropomorphic sculptures are placed alongside them. The connection with funerary rites may indicate that the pillars belong to this sphere. Whether these represent important ancestors, and whether the practice of depositing fragmented sculptures, and possibly human heads during the use of the enclosures, visualizes the addition of new members to this group, remains a question for future studies.