In 2007, Dr. Mark Holley, an adjunct professor of Anthropology at Northwestern Michigan College, discovered a possible Stonehenge-like rock formation beneath Grand Traverse Bay in Lake Michigan.

The site includes stone circles and a possible mastodon carving, which may date back around 9,000 years, from a time when the lakebed was still dry. Experts remain divided on whether it is a deliberate prehistoric structure or simply a natural formation. Its exact location has not been disclosed.

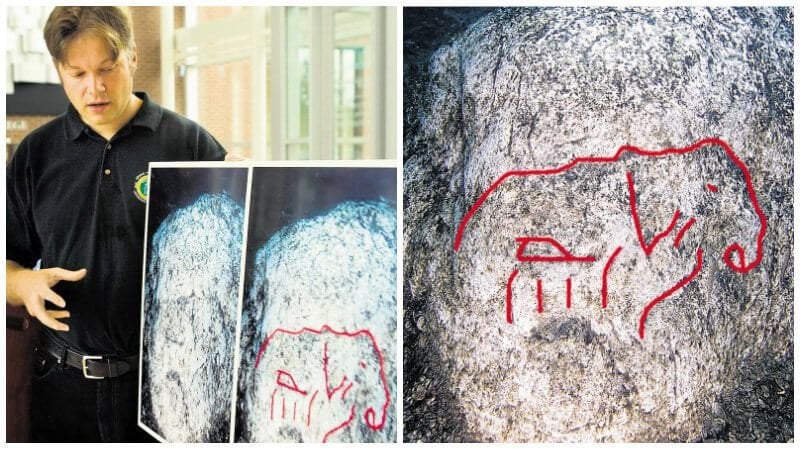

The discovery was made while Dr. Holley — who is also an underwater archaeologist — was searching for shipwrecks in the area, a once-busy maritime trade route during the 19th and 20th centuries. He first came across a rock that, according to him, contained a prehistoric engraving of a mastodon.

After further investigation, he identified an arrangement of ancient stones organized in a way that resembles the famous Stonehenge.

There is an outer ring of stones, about 12 meters in diameter, and an inner ring measuring roughly 6 meters across, both made of local granite.

They sit 12 meters below the surface of the water, and the stones are approximately 9,000 years old, making this one of the oldest structures ever discovered in North America. At that time, Holley explained, the lakebed was dry.

However, according to Holley, the stones are nowhere near the size of those at Stonehenge. Instead, they vary in size from that of a basketball to that of a compact car. There are also several stones arranged in a straight line stretching for more than a mile.

The smaller size of the stones, as Holley and other researchers have pointed out, makes the underwater structure quite different from a megalithic construction like Stonehenge. Instead, the site is “best described as a long line of stones,” Holley noted.

The discovery in Lake Michigan may, in fact, be a smaller version of a prehistoric hunting structure found beneath Lake Huron.

In a 2014 study led by John O’Shea, a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan, the Lake Huron archaeological site—about the size of an American football field—contained stone lines and human-built hunting blinds dating back 9,000 years, constructed to guide caribou.

Regarding the Lake Michigan structure, which he also visited with Holley, O’Shea told Science That Matters: “Clearly, there are a lot of stones down there. But it’s still uncertain whether it was an intentional construction.”

Another point of debate is the one-meter-tall mastodon carving found at the site, which, as Science That Matters noted, has not yet been analyzed to determine whether it was man-made or naturally formed.

Initially, many experts suggested that the carving was merely natural fissures in the rock; however, new analyses proved otherwise. The stone is about 1.5 meters tall and 1.5 meters wide, and it displays the side profile of a mastodon, complete with a long trunk and prominent tusks.

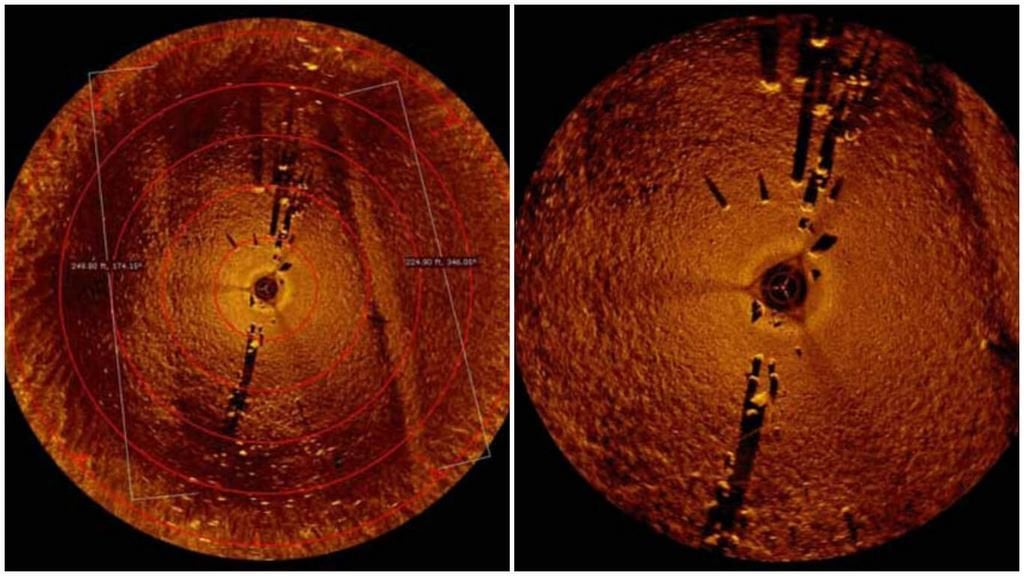

Earlier this year, a team from Northwestern Michigan College used advanced underwater imaging technology to fully map the site and reveal its true scale.

The new images replaced the initial sonar scans obtained in 2007, which showed only an irregular line of stones and did not reveal the rings or the full layout of the structure.

Holley has not disclosed the exact location of the archaeological site, which lies in an area popular among recreational divers. Instead, he first shared the location with the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa as a gesture of respect.

He noted that many experts would prefer to examine the stones in person to authenticate them, but these specialists are not always trained divers, which has slowed down the verification process.

This discovery has the potential to challenge established narratives about early human activity in North America, which have long centered on the Clovis culture — a Paleo-Indian group believed to have arrived in the region around 13,000 years ago.

Later this summer, Holley’s team will return to the site to collect sediment samples around the structure in order to determine precisely when lake levels began rising and eventually submerged the area.

If the stones were placed when the land was still dry, this could confirm human activity thousands of years earlier than previously thought in this part of North America.

Moreover, it would indicate that organized human societies existed in the Great Lakes region during the early Holocene, building large-scale structures long before the development of cities, writing, or agriculture in other parts of the world.