During the past century in Ecuador, where he lived for 60 years, Italian priest Carlo Crespi Croci managed to amass a vast collection of items from nearly all of the country’s indigenous cultures. Some objects were clearly replicas, donated by locals who revered him; however, among this collection, he also obtained a large number of enigmatic items with features that challenge traditional archaeological understanding.

Father Carlos Crespi Croci was a Salesian monk who was born in Italy in 1891. He studied anthropology at the University of Milan before becoming a priest. In 1923, he was assigned to the small Andean city of Cuenca in Ecuador to work among the indigenous people. It was here that he devoted 59 years of his life to charitable work until his death in 1982.

Father Crespi is known for his multitude of talents – he was an educator, anthropologist, botanist, artist, explorer, cinematographer, and musician – as well as his intense humanitarian efforts in Ecuador, in which he set up an orphanage and educational facilities, assisted the impoverished, gave food and money handouts, and cared deeply for the people.

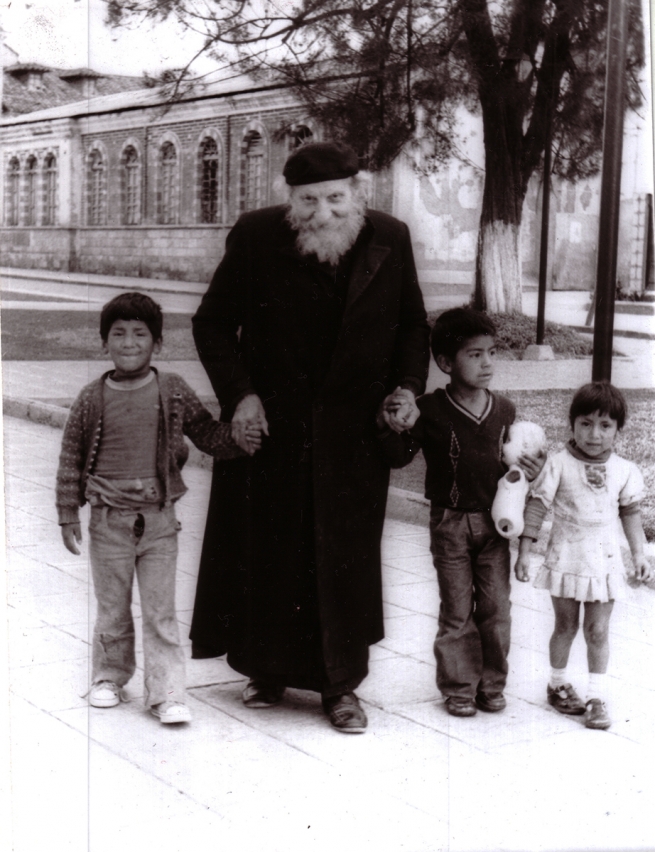

Walking around the city of Cuenca, it is clear that Crespi won the hearts of the people – today a statue of him helping a young child remains in the square in front of the church of Maria Auxiliadora, and local people old enough to have known him share stories about his intense charitable efforts. The City of Cuenca has been working with the Vatican for years to have Father Crespi recognized as a Saint.

However, it was not only the people of Cuenca that he helped. Father Crespi also had a deep personal interest in the numerous tribes of indigenous people throughout Ecuador and sought to learn about their culture and traditions, as well as to offer assistance wherever possible. People speak of his dedication to a life of voluntary poverty, sometimes sleeping on the floors of small huts belonging to indigenous people, with only a single blanket.

It was due to the dedication of Father Crespi to the people that they began to bring him artifacts as offers of thanks. These artifacts came from all corners of the country and beyond, and were representative of the works of almost all the indigenous cultures of Ecuador.

Over time, Father Crespi acquired more than 50,000 objects, many of which were kept in the courtyard of the church Maria Auxiliadora until the Vatican gave him permission to start a museum to house the collection. Unfortunately, many of the artifacts were destroyed in a arson fire in 1962.

After Father Crespi passed away, the remaining artifacts were removed and little trace of them remained. Various claims emerged as to what happened to the artifacts that survived the fire – some say they were stored in the cellar archive of Maria Auxiliadora, others say they were sold to private collectors, or that they were shipped off to the Vatican. For decades, there was little known or seen of Crespi’s precious artifacts.

Although thousands of Crespi’s artifacts are commonly considered modern sculptures or replicas of ancient items, a small subset of objects in his collection has sparked intense controversy.

Some of the artifacts are Babylonian in style, others appear to have been carved in gold with strange motifs and symbols that do not resemble objects from any South American culture. Some of the gold plates appear to show a type of ancient writing, although as far as we are aware, none of them were identified and translated.

Richard Wingate, a Florida based explorer and writer visited Father Crespi during the mid- to late-1970’s and photographed the extensive artifact collection. He said:

“In a dusty, cramped shed on the side porch of the Church of Maria Auxiliadora in Cuenca, Ecuador, lies the most valuable archaeological treasure on earth. More than one million dollars’ worth of dazzling gold is cached here, and much silver, yet the hard money value of this forgotten hoard is not its principal worth. There are ancient artifacts identified as Assyrian, Egyptian, Chinese, and African so perfect in workmanship and beauty that any museum director would regard them as first-class acquisitions. Since this treasure is the strangest collection of ancient archaeological objects in existence, its value lies in the historical questions it poses, and demands answers to. Yet it is unknown to historians and deliberately neglected in the journals of orthodox archaeology”. [Compiled by Glen W Chapman, 1998].

A video showing Father Crespi with the more controversial artifacts can be viewed below. Crespi himself says that those artifacts did not come from Ecuador but from Babylon.

The Golden Objects and the ‘Cueva de los Tayos’

In the 1960s, Hungarian-born Argentine researcher Juan Móricz became the first non-indigenous person to enter the Cueva de los Tayos, a cave—or rather, a vast network of caves—located in the Morona-Santiago region, deep in the Ecuadorian rainforest. After exploring numerous tunnels, Móricz claimed to have discovered a series of chambers filled with statues and other objects of various shapes, colors, and materials, as well as the remains of humanoid beings. The most astonishing find, however, was that in one of these chambers, hundreds—perhaps thousands—of thin metal plates, some made of gold and covered with ideograms, were stacked: a “metal library” that seemed to originate from an ancient civilization completely unknown to modern science.

In 1969, Móricz decided to reveal these wonders to the world and proceeded with utmost caution. To secure legal rights over the discovery, the first step was to formally inform the Ecuadorian government. For this, he needed a trusted lawyer, and since he was in Ecuador, he asked a senator friend for a recommendation. This is how Gerardo Peña Matheus, a prominent lawyer from Guayaquil who still resides there, became involved. In June of that year, Peña Matheus visited Móricz’s office, where they jointly drafted the report that would later be submitted to the government. Weeks later, the country’s president authorized an official expedition to document the discovery of the “Cueva de los Tayos”.

Due to his role as legal advisor, Peña Matheus was able to see the enormous underground facilities and the gigantic carved stones Móricz had described. Soon after, the press reported this extraordinary discovery, and shortly thereafter, Erich von Däniken traveled to Guayaquil to meet with Móricz and Peña.

In 1973, the Swiss author, famous for his books on ancient astronauts, published his work Gold of the Gods, based on Moricz’s findings. According to Däniken, these objects had been given to Crespi, forming the controversial part of his collection. Furthermore, Däniken claimed that the artifacts had been created by a lost civilization with the help of extraterrestrial beings. The story of Father Crespi and his artifacts gained widespread attention.

According to Moricz and Däniken, the so-called “Metallic Library” consisted of thousands of books with metal pages, each page engraved on one side with symbols, geometric designs, and inscriptions. But what happened to these mysterious books and metal plates?

Some Items Preserved, Others Missing

Currently, most of Father Crespi’s non-enigmatic collection is in the possession of the Central Bank of Ecuador. Row upon row of thousands of artifacts are stored there. They have been carefully cataloged according to their age and the culture to which they belonged—figurines, ceremonial seats, weapons, stone sculptures, ceramics, jewelry, ancient counting devices, religious icons, and even elongated skulls and shrunken human heads were part of Crespi’s impressive collection—but no metal plates.

The Metal Plates

Meanwhile, the Central Bank refused to acquire the metal plates, considering them to be fake. The metal plates are not made of gold, but of a soft, malleable metal that resembled aluminum. The engravings appear rudimentary, and many of them depict unusual figures and bizarre scenes.

The Gold Plates

A large part of Father Crespi’s collection has not disappeared, as we have seen, but was acquired by the Central Bank of Ecuador and is currently stored in the museum’s vaults. Most of Crespi’s collection consists of authentic and valuable artifacts collected throughout Ecuador.

Yet… many questions remain unanswered: where are the artifacts photographed and filmed in the 1970s, including gold sculptures, hieroglyphs, and Sumerian figures? Why are they not on display in the Central Bank of Ecuador’s storage?

The truth is that no one knows for certain. Some sources speculate that these objects were illegally acquired by private collectors; others claim they are in the possession of the Central Bank of Ecuador; and there are also those who say that certain items were taken — and later returned — by descendants of local peoples to their original places of origin.

All of this remains deeply intriguing. If the entire story of Father Crespi’s golden artifacts were false, as some skeptics suggest, then why did these objects disappear? What importance or value would they hold if they were supposedly forgeries and therefore not even made of gold?

These are mysteries for which we still have no answers.

What is certain is that Father Crespi did assemble an important collection of enigmatic archaeological items that challenge conventional explanations — objects that seem to connect our history to a past possibly far more exotic and mysterious than most people could imagine.