The history of certain ancient peoples does not fit neatly into the prevailing narrative, based on cases and documents that appear to be ignored by dogmatic archaeology and the official academic view. One example is the Sumerian King List, widely known among researchers of alternative human history, which describes semi-divine kings who ruled ancient Mesopotamia for thousands of years.

In a similar way, just as in the history of the Sumerian royal lineage, Ancient Egypt is also said to have had an exotic line of pharaonic rulers who governed for extraordinarily long periods, long before the era of mortal, human pharaohs.

This historical list is recorded in a little-publicized document known as the Turin Papyrus, a legitimate text that presents an extensive list of rulers of Ancient Egypt, from the god-pharaoh Ra to the 19th Dynasty.

Within this papyrus, we find references to the so-called Shemsu-Hor, or “Followers of Horus”—intermediary beings between the gods, described as neither fully human nor fully divine—who, according to the text, ruled Egypt for millennia.

The Papyrus

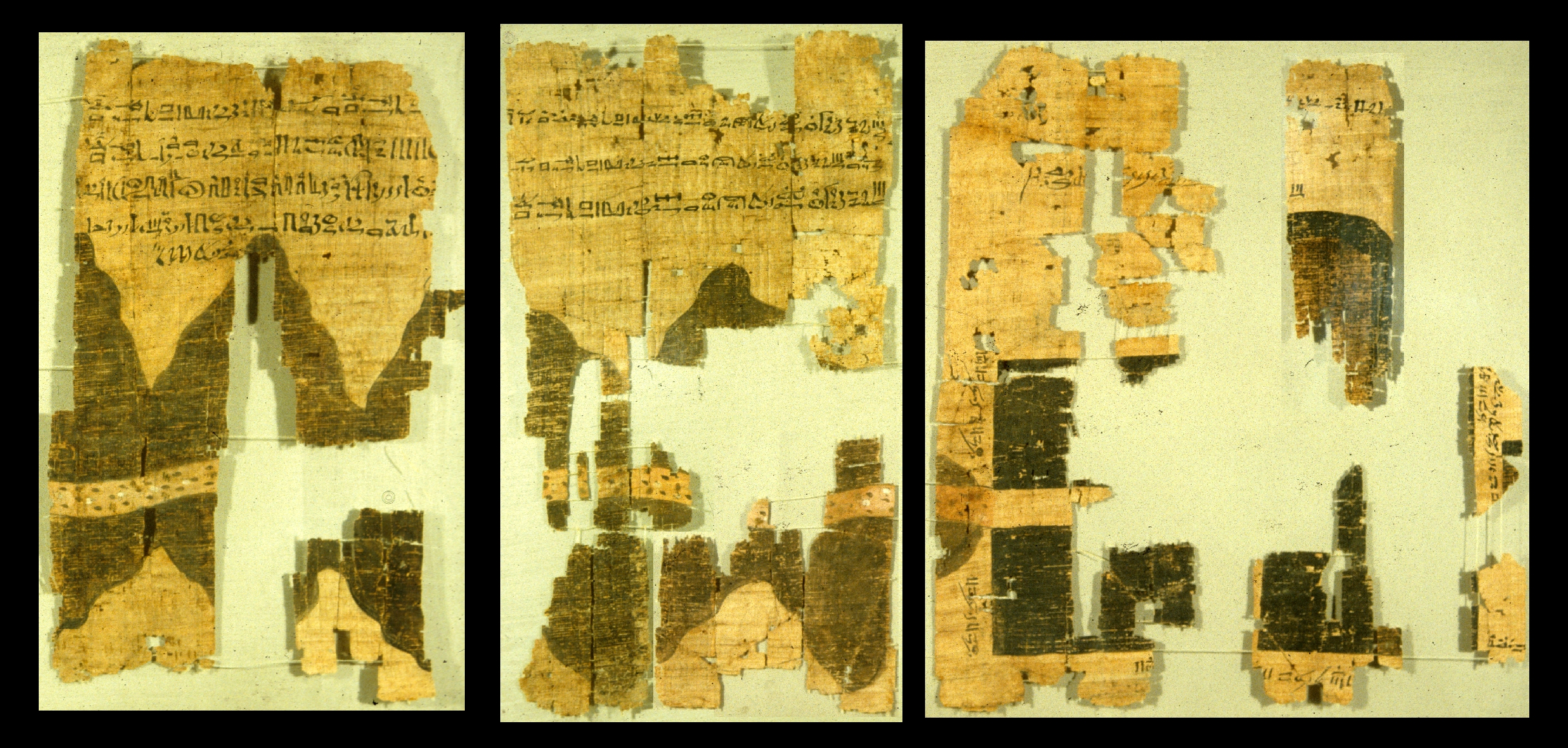

The Turin Papyrus, also known as the Turin Canon or the Turin King List, is a papyrus written in hieratic script, currently housed at the Egyptian Museum of Turin, from which it derives its name.

The text is generally dated to the reign of Ramesses II (although it may have been copied at a later period) and lists the names of the pharaohs who ruled Ancient Egypt, preceded by the gods who are said to have reigned before the pharaonic era.

The papyrus measures approximately 170 cm by 41 cm and consists of around 160 fragments, most of them very small, with numerous gaps due to the loss of significant portions of the original material.

Originally, the papyrus was an administrative tax record. However, on its reverse side, a list of Egyptian rulers was written, including mythical kings such as gods, demigods, and spirits, as well as historical human rulers.

The papyrus was discovered in 1820 in Luxor (ancient Thebes), Egypt, by the Italian traveler Bernardino Drovetti, and acquired in 1824 by the Egyptian Museum of Turin, Italy, where it was designated Papyrus No. 1874. When the box in which the document was transported to Italy was opened, the papyrus had already broken into numerous fragments.

The renowned Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion, upon examining the papyrus, was able to identify only some of the larger fragments containing royal names and produced a sketch of what could be deciphered. Subsequent efforts were made to reconstruct the list in order to facilitate its understanding and support academic research.

The Turin Canon begins with a divine era, preceding the human pharaohs. In this initial section, ruling gods appear, with Ra listed as the first king. After Ra, other gods and mythical beings are mentioned—such as Shu, Geb, Osiris, Seth, and Horus—in versions reconstructed from surviving fragments and parallels with other Egyptian traditions.

Only after this period does the era of the Shemsu-Hor (“Followers of Horus”) appear. This is followed by the historical human dynasties, which extend through the Nineteenth Dynasty.

The Non-Human Rulers of Ancient Egypt

The papyrus is divided into eleven columns, organized as follows:

Column 1 — Gods of Ancient Egypt

Column 2 — Gods of Ancient Egypt, spirits, and mythical kings

Column 3 — Lines 11–25 (Dynasties I–II)

Column 4 — Lines 1–25 (Dynasties II–V)

Column 5 — Lines 1–26 (Dynasties VI–VIII/IX/X)

Column 6 — Lines 12–25 (Dynasties XI–XII)

Column 7 — Lines 1–2 (Dynasties XII–XIII)

Column 8 — Lines 1–23 (Dynasty XIII)

Column 9 — Lines 1–27 (Dynasties XIII–XIV)

Column 10 — Lines 1–30 (Dynasty XIV)

Column 11 — Lines 1–30 (Dynasties XIV–XVII)

It is in the second column that we find the mention of the intriguing Shemsu-Hor, associated with a phase preceding the historical human dynasties.

The first column of the Turin Papyrus describes a primordial era of divine rule, listing gods who were believed to have governed Egypt before the rise of human pharaohs. Among these deities are figures such as Ra, presented as the first king, followed by other major gods of the Egyptian pantheon, including Shu, Geb, Osiris, Seth, and Horus, depending on reconstructed versions of the text. This section reflects a mytho-historical framework in which divine beings exercised kingship in a remote, pre-dynastic age.

The narrative then transitions into the second column, which introduces a more enigmatic phase of rulership associated with the Shemsu-Hor (“Followers of Horus”). Positioned between the era of the gods and the beginning of fully human dynasties, the Shemsu-Hor are presented as intermediaries, marking a transitional period between divine and human governance in Ancient Egypt.

The Shemsu-Hor

References to these mysterious figures are vague and imprecise. There are no hieroglyphs or reliefs depicting the image of the Shemsu-Hor; only references to them are found in the second column of the Turin Papyrus.

For Egyptologists, the Shemsu-Hor are legendary entities and therefore have no basis in reality. Other researchers, however, believe they played a very important role as intermediaries between gods and humans.

The renowned French archaeologist Gaston Maspero (1846–1916), one of the most influential figures in Egyptology, a discipline he helped pioneer, raised in the Revue de l’Histoire des Religions the question that undoubtedly constitutes the central enigma of this civilization: Where did the ancient Egyptians come from? What was the true origin of their religion and texts? Maspero, who perfectly combined the profile of a scholar with that of a field archaeologist, concluded that the people who developed this sophisticated set of beliefs “were already established in Egypt long before the First Dynasty, and if we want to understand their religion and texts, we must attempt to understand the mindset of those who instituted them more than seven thousand years ago.”

As we can see from the words of this French archaeologist, the idea that Ancient Egypt was founded by a very remote civilization is by no means new. However, Maspero and his ideas about the foundation of Egyptian civilization are not well received by “official” Egyptology.

What the Turin Papyrus Describes About the Shemsu-Hor

“…Venerable Shemsu-Hor, 13,420 years; Ruled before the Shemsu-Hor, 23,200 years; Total 36,620 years.”

In the second column, the Turin Papyrus briefly references the reigns of these entities.

This mention, though enigmatic and vaguely described, is one of the few sources that records the extended time these mysterious beings allegedly ruled Egypt. The timeline, spanning several millennia, raises questions about the true nature of these rulers and the historical context they belong to.

Interestingly, a similar mention to the Shemsu-Hor can be found in other ancient traditions, such as the Sumerian kings, who are also said to have ruled for extraordinarily long periods. In the Sumerian King List, for example, several kings are listed as having ruled for thousands of years, with some reigning for up to 28,000 years.

These incredible reign durations challenge the conventional historical narrative, suggesting that, like the Shemsu-Hor, the figures mentioned may have been semi-divine or, in some way, immortal. The Sumerians, much like the Egyptians, had a worldview that intertwined divinity and humanity, where the reign of certain rulers transcended the time of mortal beings.

The similarity between the Egyptian and Sumerian accounts of rulers with long reign times might indicate that both civilizations were passing down shared traditions, perhaps about a primitive civilization or beings acting as intermediaries between gods and men. These accounts, often considered mythological or symbolic, may in fact refer to a period in prehistory, far earlier than the foundations of the Egyptian and Sumerian dynasties.

Just as the Turin Papyrus describes the Shemsu-Hor, the Sumerians may have preserved fragmented memories of a distant time, where rulers were not merely human but almost divine figures, whose authority and longevity surpassed human comprehension. Both cases open the door to new interpretations of ancient history, suggesting that the narratives of these “immortal kingdoms” may be based on a lost civilization or phenomena that are still beyond our current understanding.