Stories of great floods appear in the myths of many cultures around the world. From the ancient Sumerian and Babylonian accounts to the traditions of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, and including Hindu, Greek, and Chinese legends, the theme of a catastrophic flood that destroyed humanity is a recurring archetype. In the Western world, the most well-known of these stories is, without a doubt, the biblical flood, in which Noah is instructed by God to build an ark to save his family and the animals of the Earth.

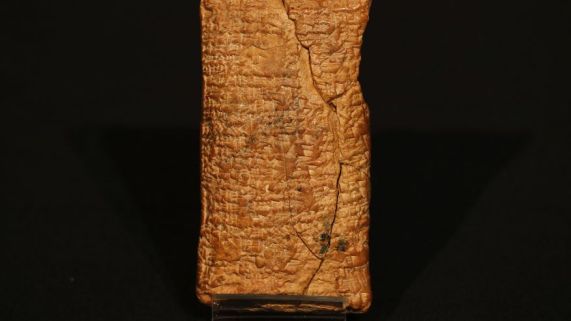

For centuries, scholars have sought to understand the origins of this narrative found in the Book of Genesis. Was it merely a parable? Or could there be older historical and cultural roots? In 2009, a surprising discovery offered a new and revealing piece to this ancient puzzle. Dr. Irving Finkel, a respected specialist in cuneiform texts at the British Museum, gained access to a small Babylonian clay tablet dated to approximately 3,770 years ago.

When Finkel began translating the symbols written in Akkadian cuneiform, he realized that the content was nothing less than a version of the flood myth—one that predates even the famous Epic of Gilgamesh and includes previously unknown details.

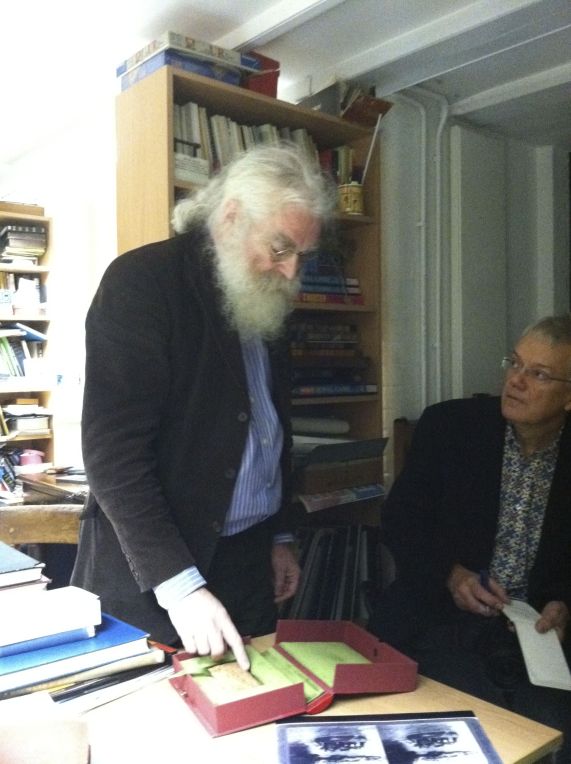

In 2009, Dr. Irving Finkel, curator at the British Museum and an authority on cuneiform writing, gained access to a Babylonian clay tablet that was in the possession of a British collector. The artifact had been inherited from the collector’s father, a former soldier who had served in the Middle East. As Finkel began translating the cuneiform signs, he quickly realized he was looking at a Babylonian version of the flood myth, written in Akkadian approximately 3,770 years ago.

The content of the tablet is a variant of the Atra-Hasis epic—a figure equivalent to the biblical Noah—and it reveals surprising details, especially concerning the construction of the ark and the preservation of animals.

The narrative contained in the tablet is at once familiar and surprisingly distinct from the biblical version. In it, the gods decide to destroy humanity with a devastating flood. However, the god Enki (also known as Ea) breaks the silence and warns a righteous man named Atra-Hasis about the impending catastrophe. To ensure the survival of life on Earth, Enki instructs Atra-Hasis to build an ark and take with him “two of every species of animal,” preserving creation.

Some of the “new” details that were discovered in this specific Atrahasis tablet (there are others) are fascinating. For example, among the many animals to be brought aboard, the list includes 44 types of snakes, 19 types of dogs, 13 types of insects, with three additional types of grasshoppers differentiated by size, 16 types of larvae, 5 types of lizards, 3 types of jackals, 11 types of scorpions, and 20 types of lions—all reflecting a genuinely Mesopotamian world of the time. Perhaps the most surprising animal category is that 23 groups of pigs are embarked, which is intriguing given later religious prohibitions.

The ark described on the tablet, however, does not resemble the rectangular ship frequently depicted in biblical illustrations. Instead, it has a round shape—like a huge coracle, a circular vessel made of reeds, traditionally still used today in regions of Iraq and India. This detail is not merely symbolic; it reflects deep technical and environmental knowledge of ancient Mesopotamia.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the tablet is the detailed description of the ark’s construction. According to the text, the vessel was supposed to be about 70 meters in diameter, a gigantic size by the standards of the time. The structure would be made from natural materials such as reeds and braided ropes, and waterproofed with bitumen. The interior would have compartments to house the animals, which would enter in pairs. The construction was not intended for navigation but only to float and withstand the violence of the flood — a kind of survival capsule in the face of imminent doom.

This precise description makes the tablet what can be considered the oldest known “shipbuilding manual” in history. More than that, it raises the hypothesis that the idea of a universal flood and an ark intended to preserve life is much older than the version presented in the Old Testament.

The discovery of the tablet reopened fundamental debates about the origin of the flood myth. It appears that this story did not originate among the Hebrews but was inherited from earlier cultures such as the Babylonians and Sumerians, where similar versions circulated centuries before. It is possible that during the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE, the Jews came into contact with these narratives and adapted their elements into what we now know as the Genesis account.

“I’m 107% convinced that the ark never existed,” said Irving Finkel at the time.

inkel described the clay tablet as “one of the most important human documents ever discovered,” and his conclusions are set to have an impact in the world of creationism and among ark hunters, where many believe in the literal truth of the biblical account, and countless expeditions have been organized to try to find the remains of the ark.

Dr. Finkel published a book based on his significant discovery: The Ark Before Noah, which reveals firsthand the translation of an extraordinary cuneiform tablet. The work is an engaging blend of archaeology, philology, ancient history, and almost “detective-like” investigation, written in a way that is accessible even to a lay audience.

Finkel begins with his own experience upon receiving the artifact from a private collector and details the process of translating the cuneiform signs on the tablet, which is written in Akkadian. From there, he delves into the rich mythological tradition of Mesopotamia, explaining how flood stories were common in Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian literature—and how these stories likely influenced the Book of Genesis, written centuries later.

Thus, the central elements of the myth—a man chosen by a deity, the construction of an ark, animals in pairs, and the flood that sweeps the world—reveal themselves as part of an ancient cultural tradition, reinterpreted by different civilizations over time. The small clay tablet, therefore, not only retells a familiar story but also helps us understand its deep origins and forgotten paths.

why does it have to be 1 Ark.