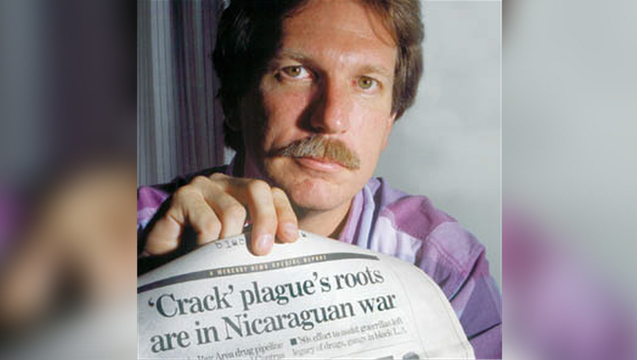

Gary Webb knew that his report would cause a stir. The article he wrote suggested that a rebel army in Latin America, backed by the United States, was supplying the drugs responsible for devastating some of Los Angeles’s poorest neighborhoods—and, crucially, that the CIA was aware of it.

The Dark Alliance series, published by the San Jose Mercury News in 1996, claimed that the Contra rebels in Nicaragua were shipping cocaine to the U.S. This cocaine, later turned into crack, flooded Compton and South-Central Los Angeles in the mid-1980s, causing a devastating epidemic. Webb also revealed that the profits from these drug sales were, directly or indirectly, used to finance the Contras, and that the CIA not only knew about it but allegedly turned a blind eye to the operation.

Webb’s investigation sparked a storm of reactions. Black communities in Los Angeles were shocked to realize that their own government might somehow be connected to the crack epidemic destroying their families and neighborhoods. The U.S. government found itself forced into a defensive stance, while much of the press attacked Webb instead of delving deeper into the scandal he had uncovered.

Gary Webb began his journalistic career as a teenager, writing for his school newspaper in Indiana. It was there that he met his future wife, Sue. The family later moved to Ohio due to his father’s work, and Webb never completed a journalism degree, starting his professional career at the Kentucky Post in 1978. He married Sue a year later, and after a decade of experience at various Ohio newspapers, he moved to California, where he was hired by the San Jose Mercury News.

Webb quickly distinguished himself for his investigative rigor. He was unafraid to confront powerful political and financial interests in pursuit of the truth. His courage in exposing one of the most dangerous connections between politics, crime, and intelligence was, tragically, also the cause of his death.

The story that would make Gary Webb known—and which, according to many, contributed to his unfair downfall and untimely death—began more than a decade earlier. In 1979, the Sandinista National Liberation Front (commonly known as the Sandinistas) overthrew Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Debayle. Fearing the creation of a Communist state allied with Cuba and the Soviet Union, the U.S. government under President Ronald Reagan began funding and arming groups of rebels opposed to the Sandinistas—known as the Contras or Counterrevolutionaries.

In his book A Twilight Struggle, Robert Kagan, one of the architects of U.S. foreign policy in Latin America during the Reagan administration, wrote that when Americans began their covert support of the Contras, the armed militants numbered fewer than 2,000. By the end of 1983, that number had grown to 6,000. Critics of U.S. support for the Contras highlighted the groups’ numerous human rights abuses—and this was essentially the heart of Webb’s story.

Webb arrived at the Contra story relatively late. There had already been press mentions of the Contras’ link to drug trafficking in the U.S.—and, by extension, possible CIA involvement. But what Webb did, that no one else had done, was trace the entire supply chain—all the way to the poorest streets of Los Angeles. He showed what happened to the cocaine after it was smuggled in by the Contras, focusing on its human impact, and revealed where the profits from the sales ended up.

He summarized the core of his Dark Alliance series like this: “It is one of the most bizarre alliances in modern history. The union of a U.S.-backed army attempting to overthrow a revolutionary socialist government with the uzi-wielding ‘gangstas’ of Compton and South-Central Los Angeles.”

Webb also wrote that crack was virtually nonexistent in the city’s Black neighborhoods before “members of the CIA’s army” began supplying it at rock-bottom prices in the 1980s.

“For the better part of a decade,” he wrote in the introduction to the first piece in the trilogy, “a drug ring in the San Francisco Bay Area sold tons of cocaine to the Crips and Bloods street gangs of Los Angeles and funneled millions in drug profits to a Latin American guerrilla army run by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.”

He reported on the cocaine trafficking trial of a former Contra leader named Oscar Danilo Blandon Reyes, who testified that the CIA agent commanding the guerrilla army had told them that “the ends justify the means,” and that in 1981 alone they sold almost a ton of cocaine, with the profits going to the Contra revolution.

Webb’s series was published on the fledgling website of the San Jose Mercury News, but it did not immediately cause a sensation.

Webb’s then-wife, Sue, recalls that he came home extremely excited while finishing Dark Alliance. “He worked from home a lot,” Sue said. “He said, ‘You’re not going to believe what I discovered.’ He was maybe a little nervous but very excited. No one had ever gotten this far with this story. No one had traced it to where the drugs were actually going, and that was the first indication that we were probably looking at a very big story. It made me a little nervous too.”

When Webb published his story, the family was about to go on vacation to North Carolina and Indiana. The article came out shortly after their return, and Sue remembers that at first, there was hardly any reaction. “It was really quiet,” she said. “Then the phone started ringing.”

Nick Schou, who was then a rookie reporter in Southern California, heard Webb interviewed on the radio before reading Dark Alliance. He was impressed by Webb’s effort to expand a story that many journalists at major national papers had tried and failed to cover. Reading the series online, Schou was struck by how much effort the Mercury News team had put into giving the story impact on the internet.

“It certainly was one of the most ostentatious early journalism exposes published online,” Schou says. Because the Mercury News was in Silicon Valley, the paper had a talented web and graphics team. When you visited the site, Schou says, “all you saw was the CIA seal with a crack user superimposed on it and very ominous lettering reading ‘Dark Alliance.’”

Webb became something of a celebrity. A publicist at the Mercury News handled media inquiries. Schou recalls that when he first contacted Webb, he was in Washington, D.C., for a talk show appearance promoting the story. Unfortunately, that also contributed to his downfall—Gary Webb had become the story itself. “Once the series was attacked, Webb obviously had his entire career and credibility invested in it. Everyone else at the Mercury News found it easy to step back from the spotlight and let him take the brunt of the criticism. They didn’t really support the story once the papers of record began tearing it apart.”

Talk radio—especially African American talk radio—helped spread Webb’s story. There were demonstrations in Los Angeles, and in the U.S. Congress, the Black Caucus began discussing Dark Alliance in session. Legislators and community leaders demanded answers.

According to Schou, probably for the first time in history, then-CIA director John Deutch flew to Los Angeles to appear at a gymnasium in South Central, promising a full investigation into the story and its implications—while denying that the agency had deliberately introduced crack into the area. “He was booed and jeered,” Schou recalls.

After spending three years investigating the case, Webb stated that he was more convinced than ever that the U.S. government’s responsibility for the drug problems in South Central Los Angeles was “greater than I ever wrote in the paper.” However, Nick Schou notes that Dark Alliance was not a perfect piece of journalism. “There were many loose ends in the story, but it presented interesting characters and made some very bold claims. If the press had really dug in, many people at the CIA could have been fired. But none of that happened.”

Schou points out that one of the key mistakes, in his opinion, was the way the story was presented graphically — with the CIA seal and the image of a crack user — which led the public to assume that the agency had created crack, something the report never claimed. Additionally, the opening paragraphs tended to overstate the evidence contained in the series.

Webb’s ex-wife, Sue, says that the reaction of the mainstream press was more painful than anything else, but, as if that were not enough, the newspaper itself began to distance itself from the story. “He said he couldn’t believe what they were writing. He was shocked. He kept defending himself in interviews, and it was overwhelming for him when the Mercury News began to back off.”

In May 1997, Jerry Ceppos, executive editor of the Mercury News, wrote an article admitting deficiencies in the Dark Alliance series, stating that it “fell short” of the newspaper’s standards. In the eight months preceding Ceppos’s public retraction, Sue says the paper supported Webb one hundred percent. “He had book proposals and even a movie, but he said it seemed like the paper wanted him to continue with the story — to go back to Nicaragua to investigate further.”

But Webb did not want to disappoint the paper; he did not want to step away to focus on a book or movie. He was very conscientious. Sue believes that his eventual departure from the paper — after being removed from the series and relocated to a suburban office — and the impossibility of landing another significant job in journalism led him to a period of depression that culminated in suicide. “Gary suffered from depression intermittently,” Sue said. “I was married to him for 21 years and knew him for 27. But it was nothing serious. He took antidepressants once or twice. But he loved writing and being an investigative reporter; that was his passion. So yes, I believe all of this led to a deep depression and to taking his own life. Our marriage ended, he became increasingly depressed, there were extramarital affairs… he even talked to his mother about not being able to support himself as a journalist on the night before his death.”

Gary Webb committed “suicide” on December 10, 2004, at his home in Carmichael, California. The night before, he typed farewell letters to Sue and his three children and left a handwritten note on the door instructing anyone who entered to call the police. According to the official version, he then shot himself in the head.

However, the circumstances surrounding his death have raised silent questions over the years. Webb was not an ordinary journalist: he had exposed deep connections between drug trafficking, clandestine operations in Central America, and the structures of the U.S. government itself — including the CIA. His work not only embarrassed the agency but threatened to reveal a historical pattern of covert operations indirectly funded by drug trafficking.

After the publication of Dark Alliance, Webb was systematically isolated professionally, attacked by major media outlets, and practically banned from high-level investigative journalism. To some observers, this process of reputation destruction seemed less a legitimate journalistic debate and more a coordinated neutralization operation.

The fact that Webb died just after years of extreme pressure, hostile media scrutiny, and total professional blockage raises an uncomfortable question: to what extent was his death the result of personal depression — and to what extent was it the predictable outcome imposed on someone who dared to go too far?

Even after his death, part of the mainstream press treated Webb as a discredited reporter, avoiding revisiting the core content of his allegations. For critics of this silence, the pattern is familiar: expose the messenger, bury the message. In cases involving intelligence agencies, the truth rarely appears directly — it usually emerges in the gaps, the retreats, the coincidences, and the tragic fates of those who spoke too much.

After Webb’s suicide, Nick Schou read his obituary in the LA Times, which called him a discredited reporter. Disturbed, he decided that someone needed to tell the full story. Thus was born Webb’s biography, based both on his own work and on Schou’s detailed investigation of Dark Alliance, which later served as the basis for the film Kill the Messenger.